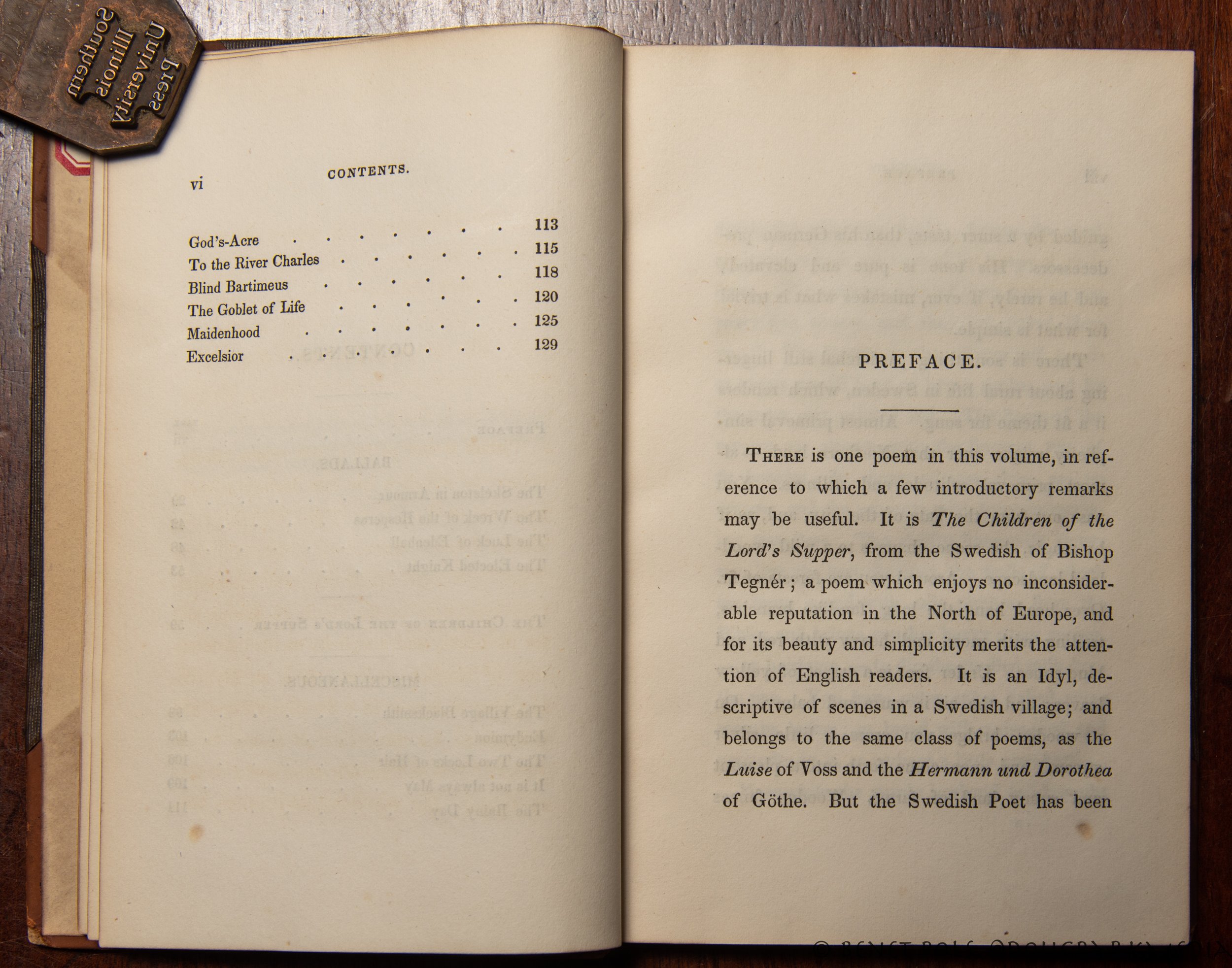

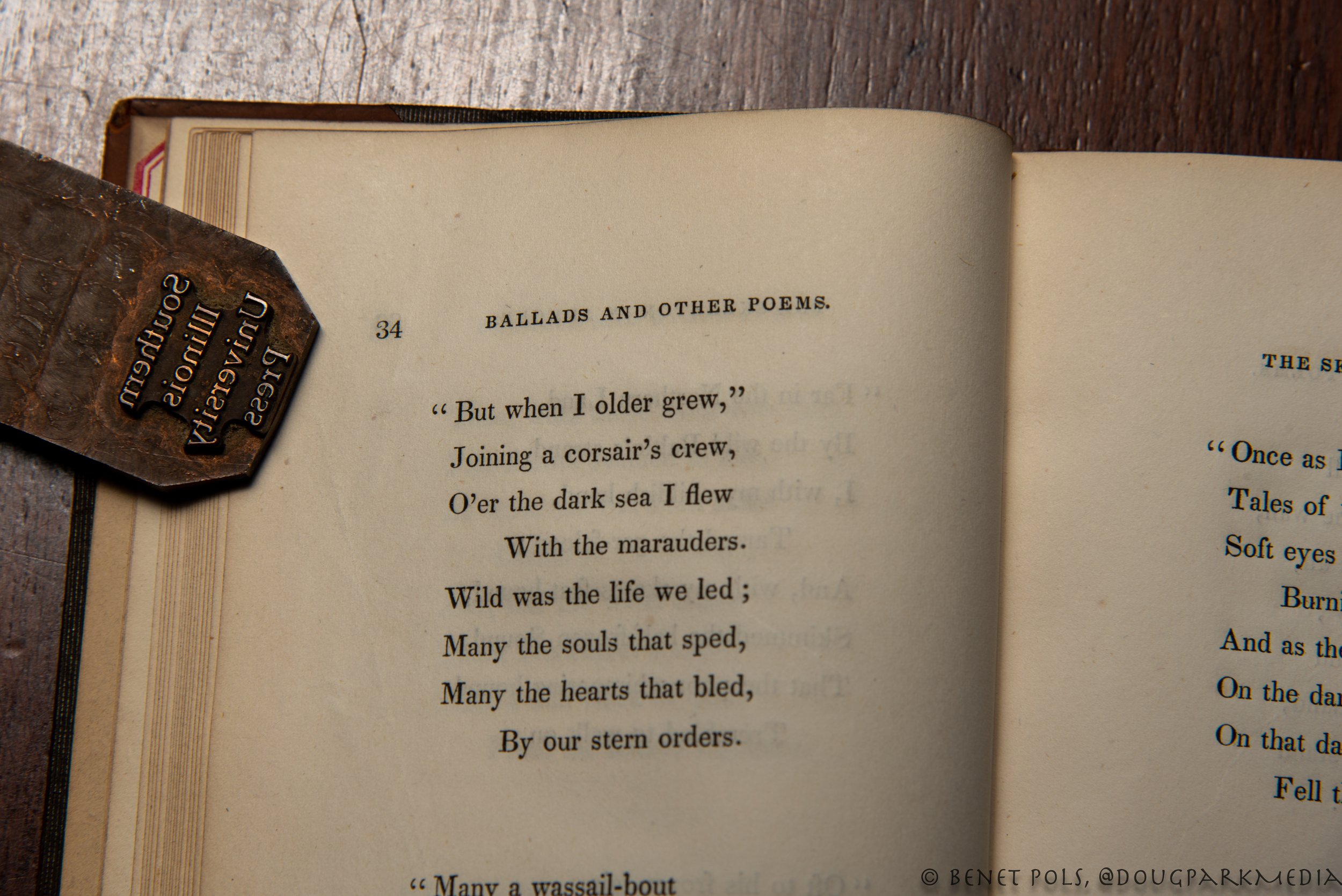

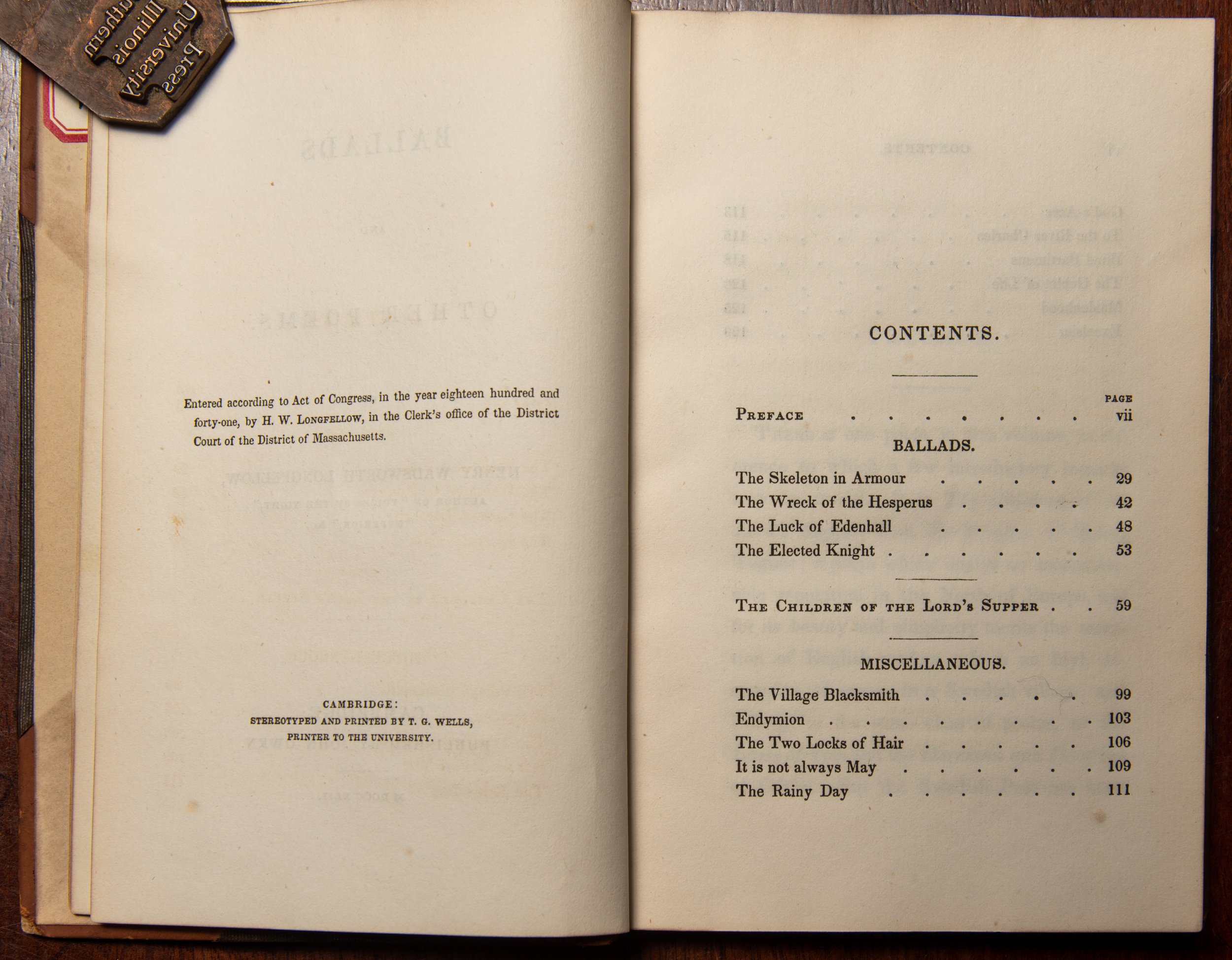

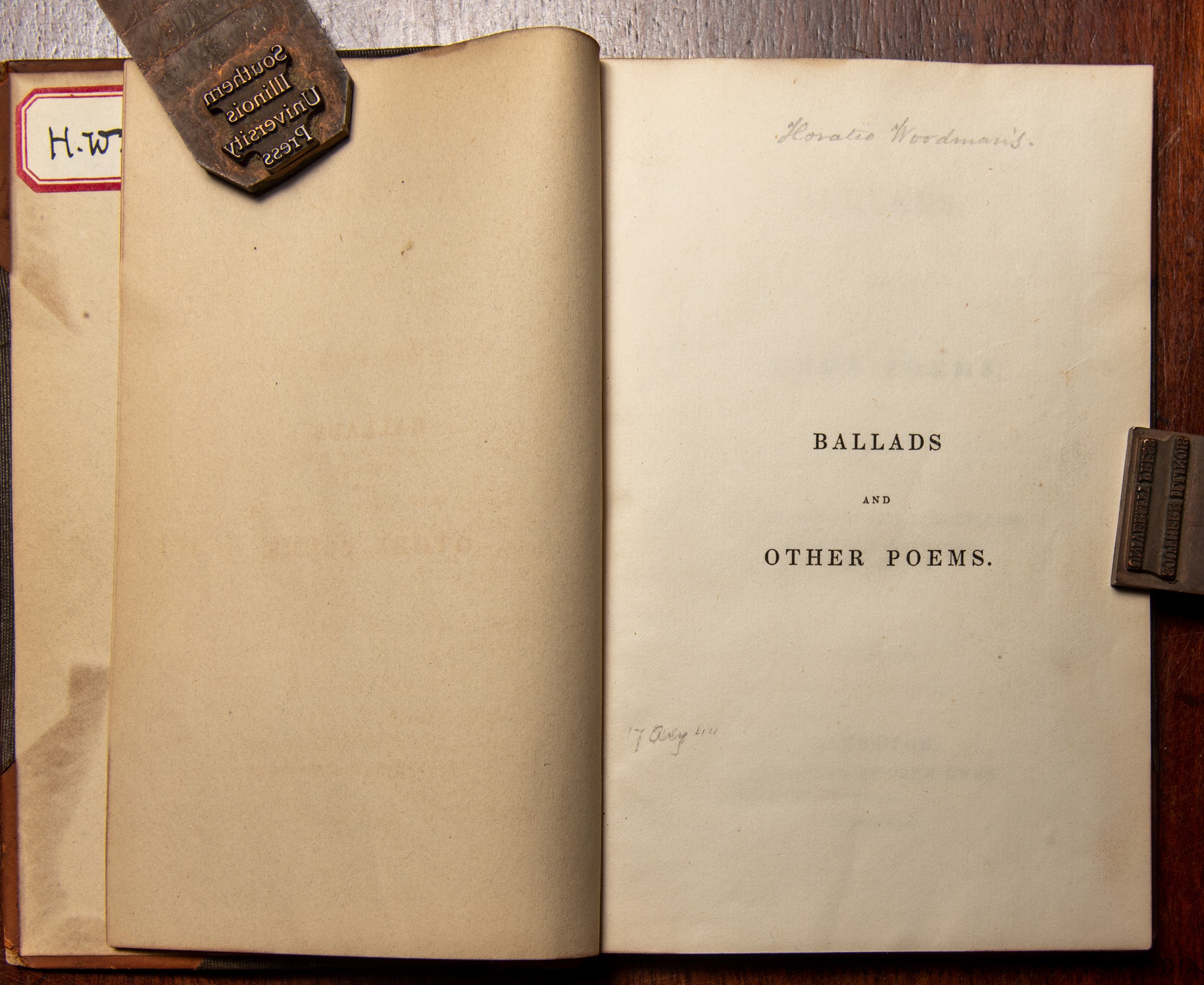

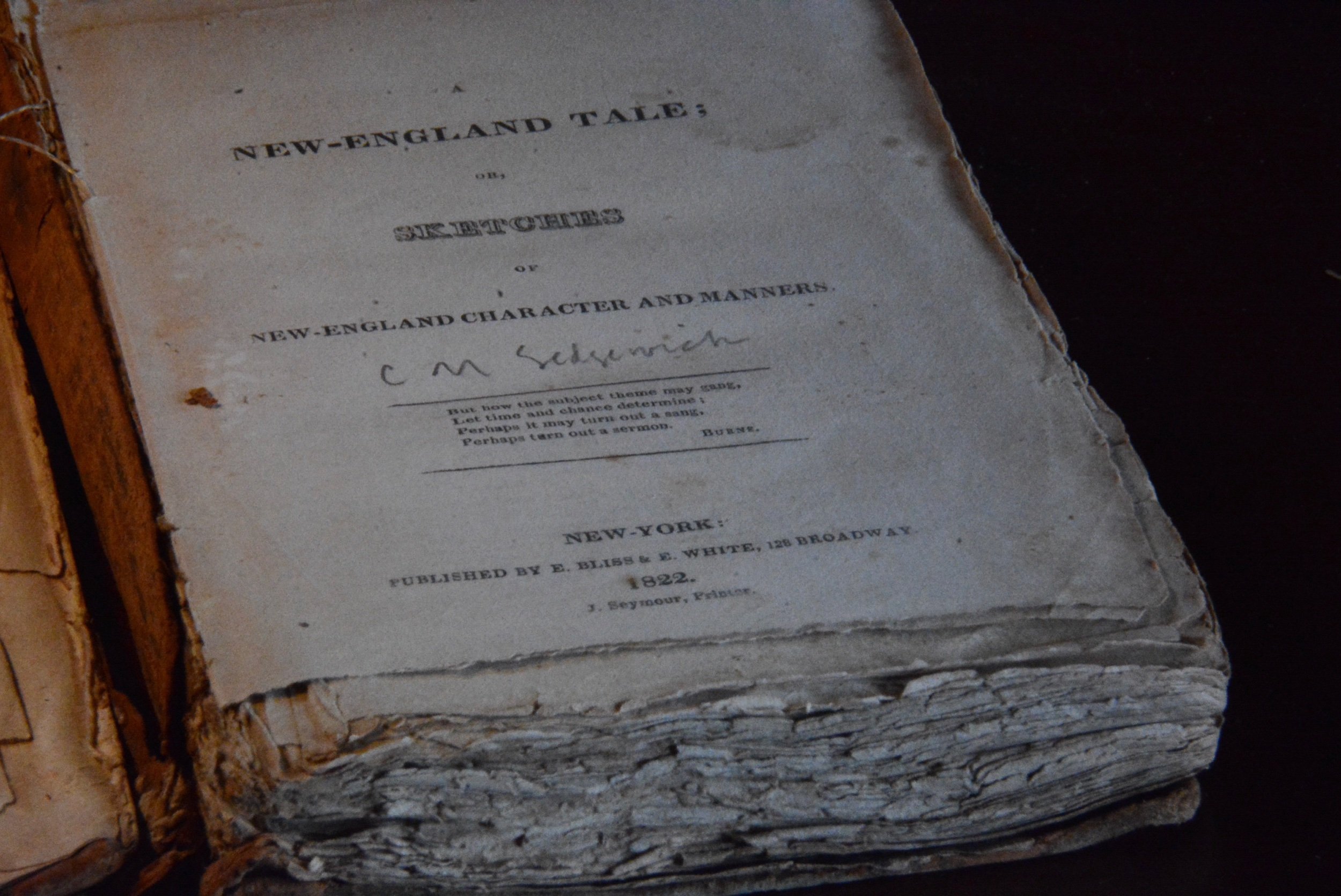

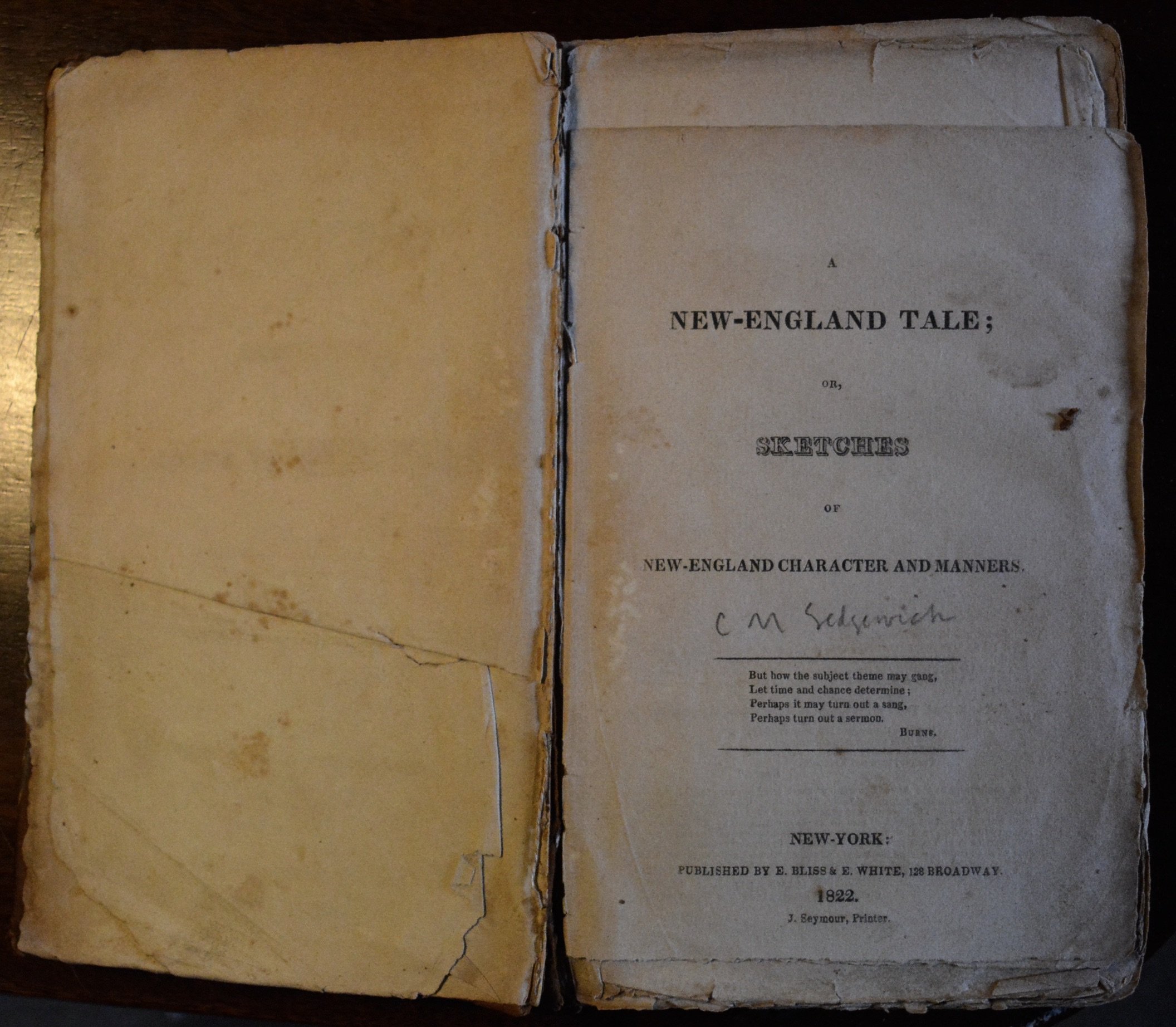

For several years now I have been intending to write him. I pass his home frequently on the Highland Road on my commute to and from work. I often walk the road from Pleasant Hill Road to Bunganuc Road. I eyeball the Bunganuc Stream’s outlet into Maquoit Bay winding by a legendary house on posts hard on the stream side. On the walk back, if the sun is in the right place its light is refracted through the slats on the cupola of Professor McKee’s barn. Along the road are signs noting that his property, which extends down across the road and down to Bunganuc Stream, is private but may be crossed with permission of the owner. The signs provide the name, John McKee. For several years now, since discovering that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in one of his earliest published works, written under the pseudnym George F. Brown, referred to us natives of Brunswick as Bungonuckers, I have wanted to walk along Bunganuc Stream to see what triggered Longfellow to decide that this little stream encapsulated the essence of our community.

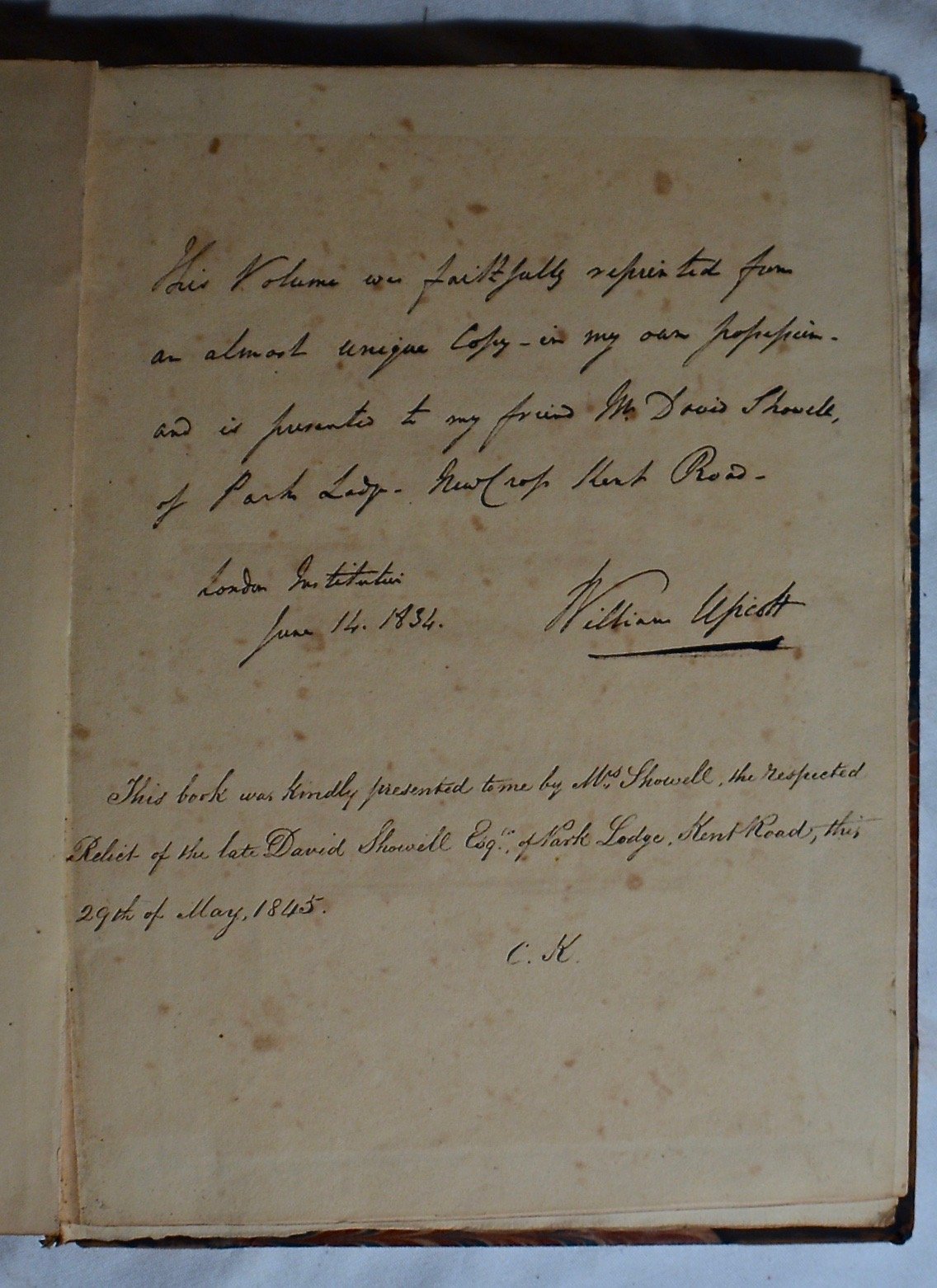

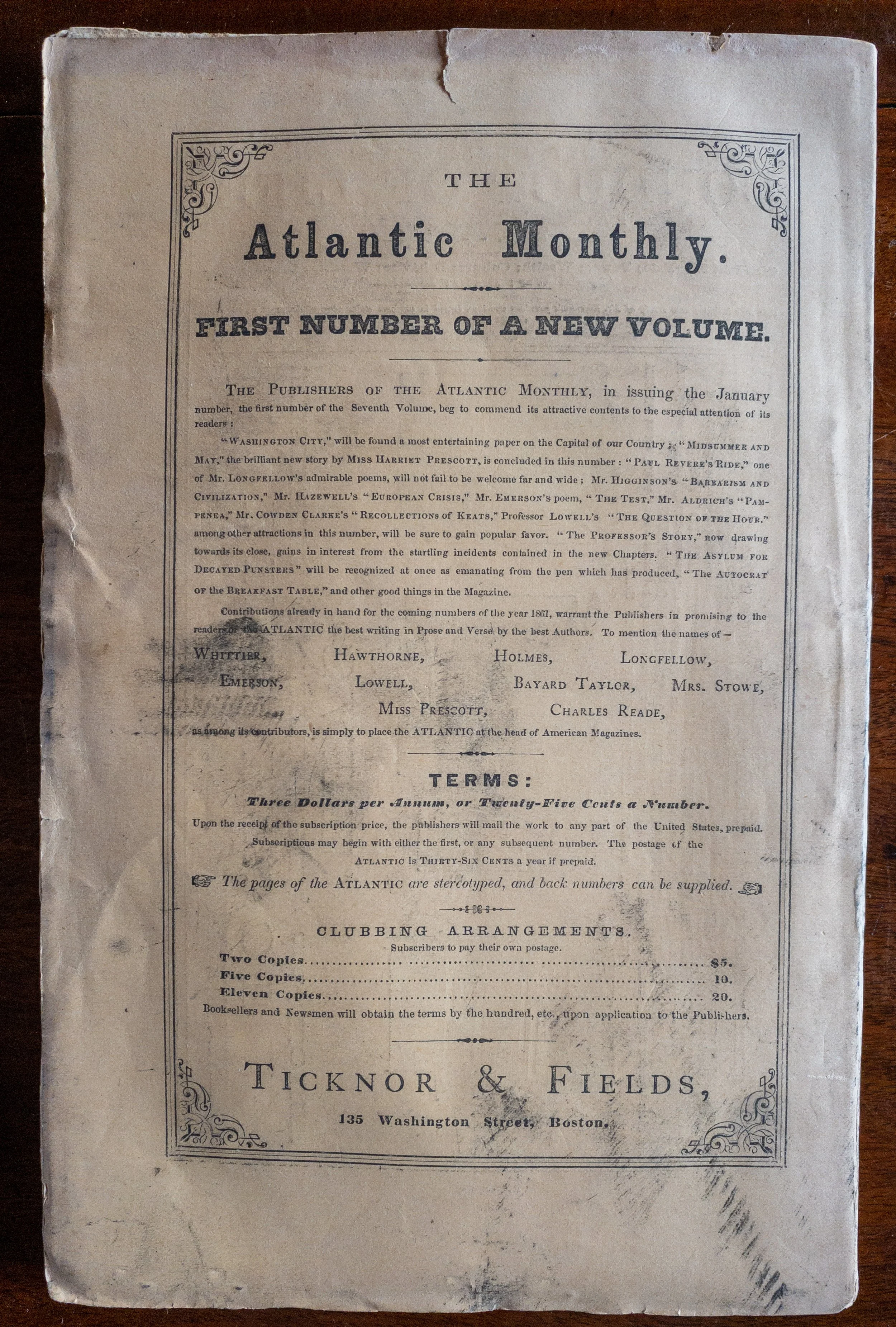

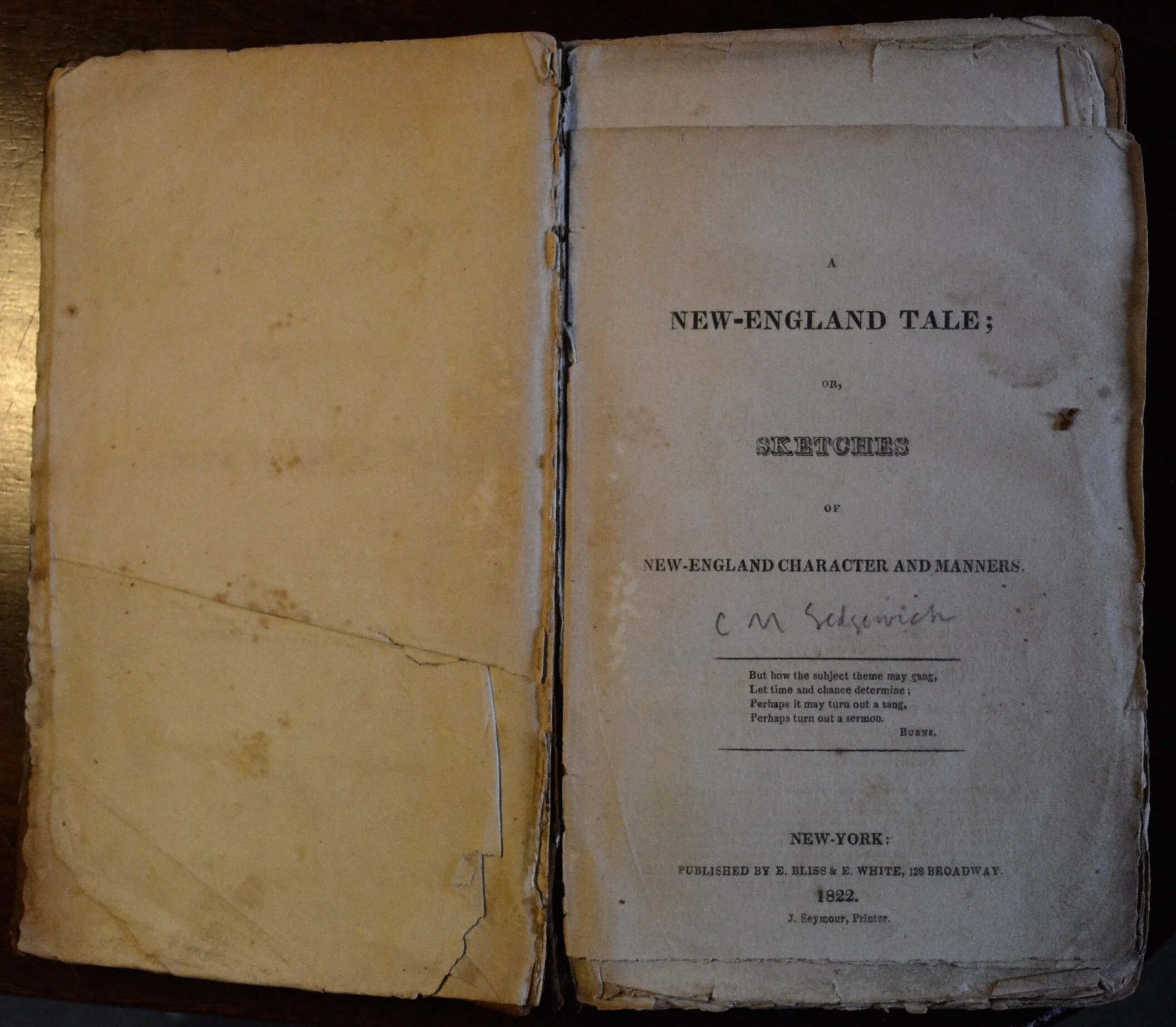

“Having very little business of their own, they have ample leisure to devote to the affairs of their neighbors; and it is said, that even to this day, if a Bungonucker wishes to find out what is going on in his own family, the surest and most expeditious way, is to ask the person who lives next door.” The Wonderous Tale of the Little man in Gosling Green. The New Yorker, 1834.

Today as I wondered what to do with my can of PBR, I wondered again about John McKee and what approach I might take to ask his permission to cross his land to wander down by Bunganuc Stream.

It seems now I never will:

John McKee, Associate Professor of Art Emeritus, died on March 8, 2023, in Brunswick, Maine.

(The following notice was shared by President Rose on March 13, 2023)

I’m sorry to inform the Bowdoin community that Associate Professor of Art Emeritus John McKee died on Wednesday, March 8, 2023, in Brunswick, after a period of declining health.

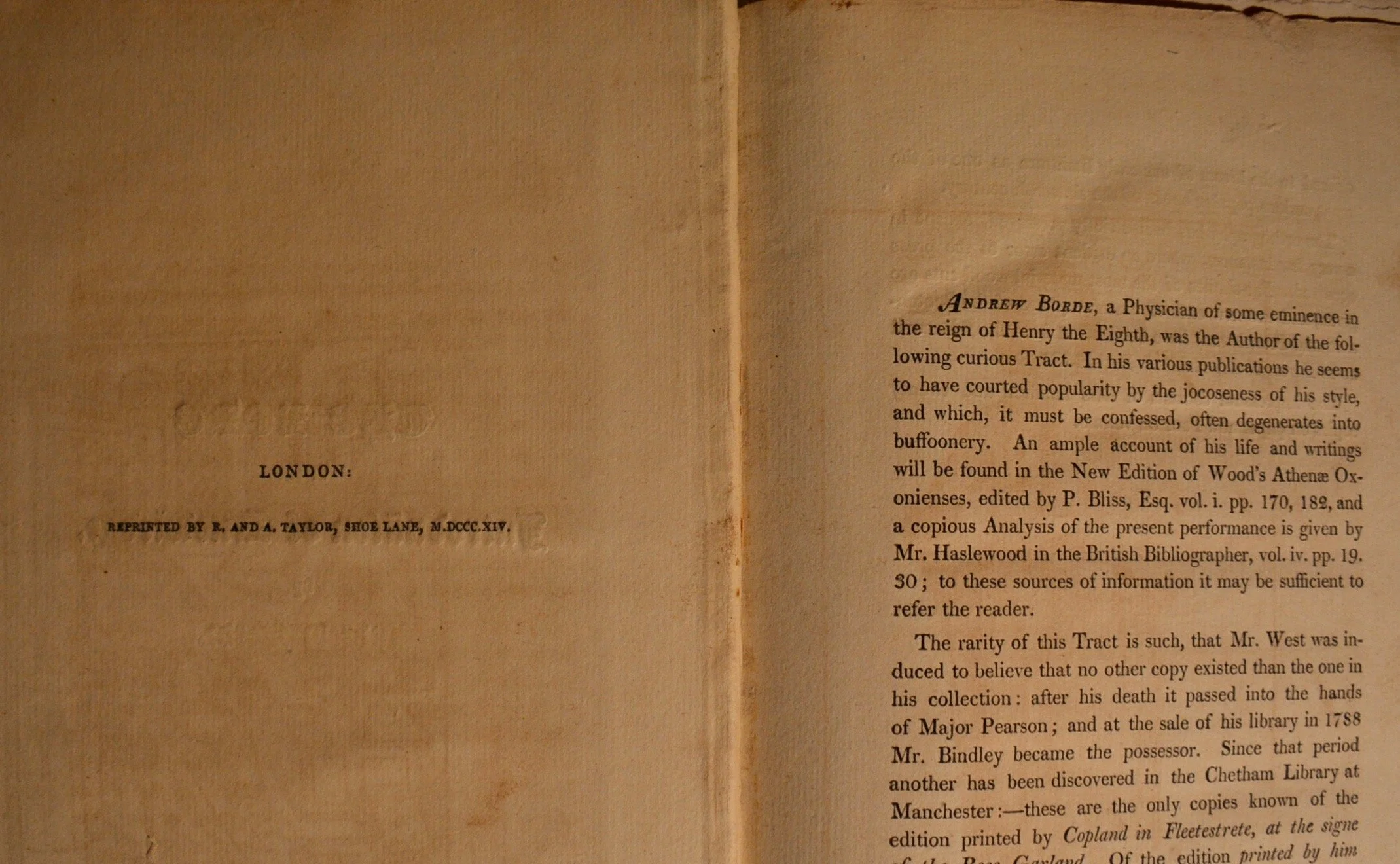

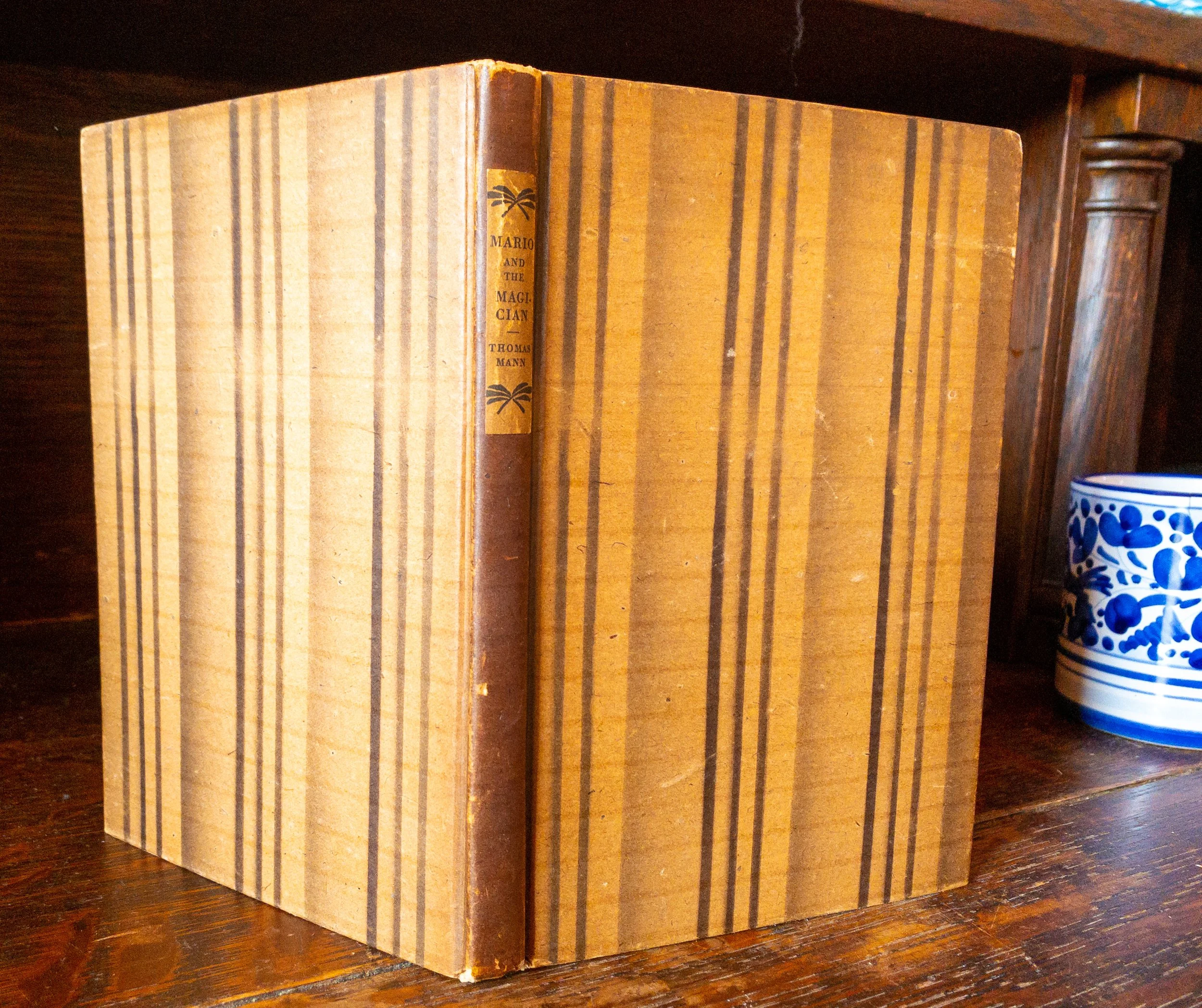

John was born on October 20, 1936, in Evanston, Illinois, and grew up in Palatine, Illinois. He graduated summa cum laude from Dartmouth as a music major in 1958 and as a member of Phi Beta Kappa. He earned a master’s degree at Princeton in 1962, where he did additional graduate work and was an assistant instructor in French. His black-and-white documentary film about undergraduate life at Princeton, “Princeton Contexts,” won the Silver Award (highest in the category) at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1962—an early indication of his talents as both a photographer and filmmaker.

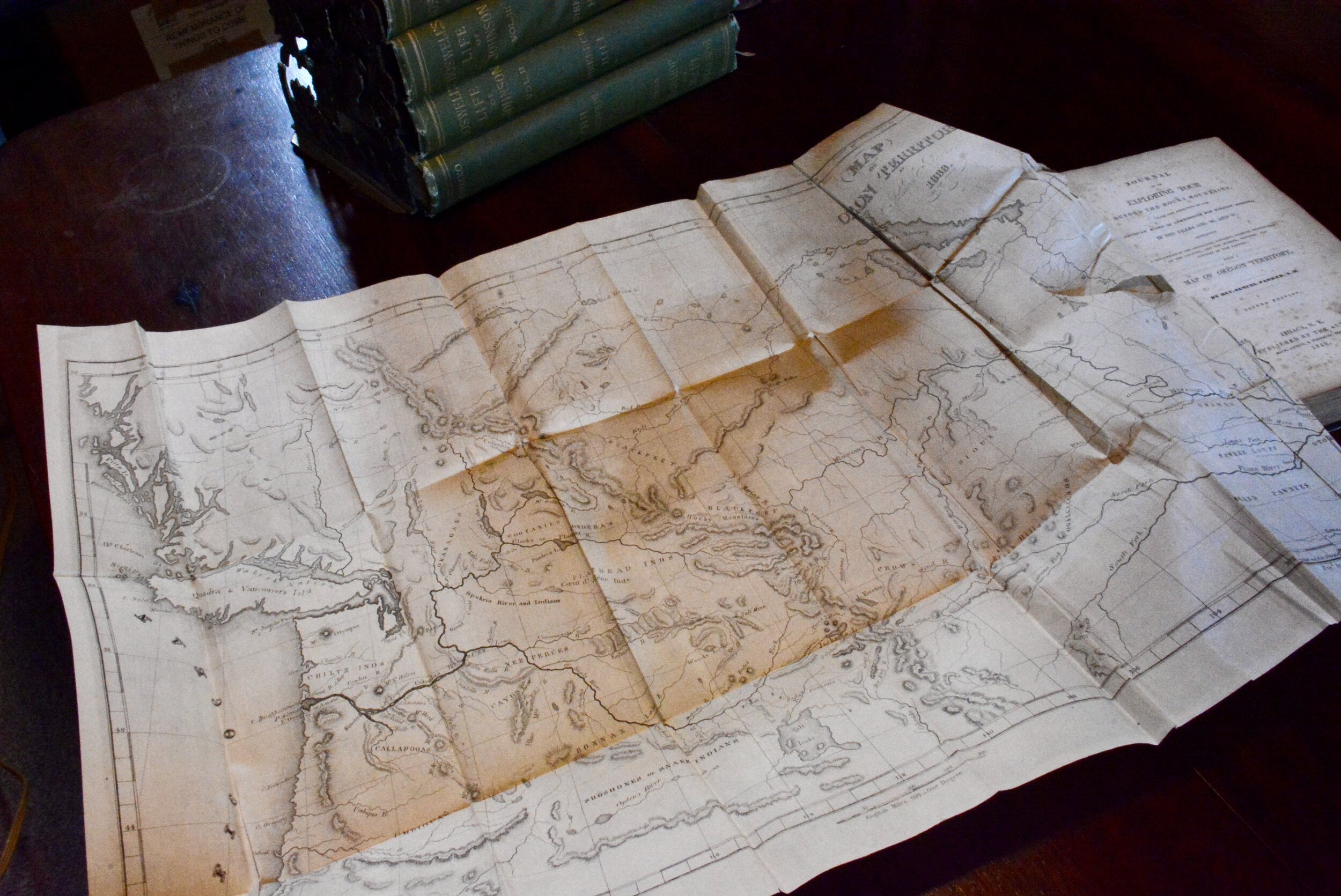

John came to Bowdoin in the fall of 1962 as an instructor in Romance languages, a position he held until 1966. His photographs and accompanying catalogue for a 1966 exhibit at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art—“As Maine Goes…”—revealed some ugly truths about the environmental consequences of pollution, seaside dumps, and unchecked development along the coast. It was widely recognized as a catalyst for the environmental movement and for legislation banning billboards on public roadways in Maine. Following the exhibit, John was named the director of the Bowdoin Center for Resource Studies in 1966 to explore land-use issues along the Maine coast. The extraordinary photographs from “As Maine Goes…” also won him the National Conservation Communicator of the Year Award from the National Wildlife Federation.

His second exhibit of photographs at our museum—”Hands to Work and Hearts to God,” about Maine’s Sabbathday Lake Shaker community—was recognized by the Maine Commission on the Arts and Humanities with the 1973 Maine State Award for images that “…summon poetry out of simple things and do not yield to the obvious or the picturesque.” A major retrospective in 1984, “Photographs 73–83 John McKee,” also received critical acclaim for John’s artistry. His influence as a teacher was on display in a 1994 exhibit and catalogue of the work of his former students, “Bowdoin Photographers: A Liberal Arts Lens.”

John was a lecturer in the art department from 1969 to 1987 and an associate professor of art from 1987 until 2001, when he retired and was voted emeritus status. His former students established the John McKee Fund for Photography in 2002 to honor his legacy.

John’s faculty file contained a sealed envelope to be opened upon his death. Inside is a note, written in December 1990, informing the dean of the faculty that he did not want a memorial service: “Anybody who wants to, might some good day go for a quiet walk and enjoy looking about.” This was followed by “If a memorial minute must be read at some faculty meeting, it better not last more than sixty seconds.”

John’s life and career have had a lasting impact on the College, on Maine, and in his field. We join with his former students, friends, and colleagues in expressing our gratitude for the many ways he encouraged us to see the world around us with new eyes.

Sincerely,

Clayton